| |

bolster ends represented by concentric circles in relief (Fig. 8) were somehow incorporated into the walling at the monumental entrance to the Palatial Complex. This discovery has wider implications for relationships between Kerkenes and rock-cut architectural façades in the Phrygian Highlands much further to the west. Similar architectural embellishment has not been reported from Gordion or from the Ankara region. Progress in mending the large stone idols was greatly facilitated by the orderly migration of all the fragments into the spacious new workshop.

A Seljuk Coin of Sultan Keyhüsrev II

Tantalisingly, the Kale, so called because of the Byzantine castle that was constructed over the remains of the earlier acropolis, is called Keykavus Kale on modern maps. Rare evidence for Seljuk activity was a silver dirhem of Keyhüsrev II (AD 1237-1246), minted at Sivas (Fig. 9), which was picked up on the surface.

Iron Age Metals

Ben Claasz Coockson was able to complete the task of drawing the architectural iron objects excavated at the entrance to the Palatial Complex (Fig. 10). These included the two complete iron bands, discovered with some large nails still in place, that perhaps held together monumental wooden doors.

Joseph Lehner, a graduate student at the University of California at Los Angeles, has begun an innovative study of the Kerkenes metals (Fig. 11). Samples taken by invasive and non-invasive techniques are currently being analyzed to determine their preserved metallic structure as well as their elemental andisotopic compositions. One facet of this study involves precise measurement of lead isotopes to assess probable provenance of the raw materials used to manufacture the finished metal objects. This study will shed light on the ancient technological practices employed by Iron Age craft specialists and also form a crucial body of information relevant to social and economic patterning within the ancient city. Additionally, we may begin to understand how residents of this ancient capital participated in broad regional exchange networks present in the first half of the sixth century BC.

The Kerkenes Gallery at the Yozgat Museum

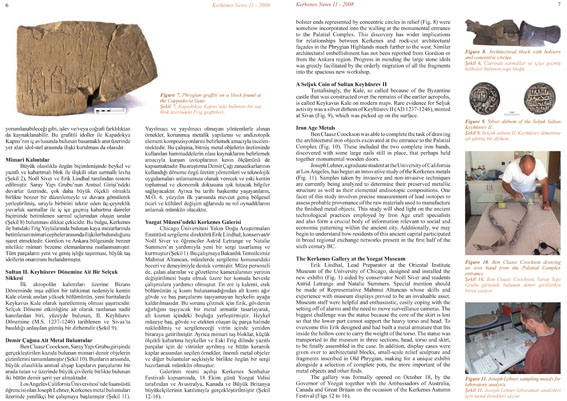

Erik Lindhal, Lead Preparator at the Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago, designed and installed the new exhibit (Fig. 1) aided by conservator Noël Siver and students Astrid Letrange and Natalie Summers. Special mention should be made of Representative Mahmut Altuncan whose skills and experience with museum displays proved to be an invaluable asset. Museum staff were helpful and enthusiastic, easily coping with the setting off of alarms and the need to move surveillance cameras. The biggest challenge was the statue because the core of the skirt is lost so that the lower part cannot support the heavy torso and head. To overcome this Erik designed and had built a metal armature that fits inside the hollow core to carry the weight of the torso. The statue was transported to the museum in three sections, head, torso and skirt, to be fi nally assembled in the case. In addition, display cases were given over to architectural blocks, small-scale relief sculpture and fragments inscribed in Old Phrygian, making for a unique exhibit alongside a selection of complete pots, the more important of the metal objects and other finds.

The gallery was formally opened on October 18, by the Governor of Yozgat together with the Ambassadors of Australia, Canada and Great Britain on the occasion of the Kerkenes Autumn Festival (Figs 12 to 16). |